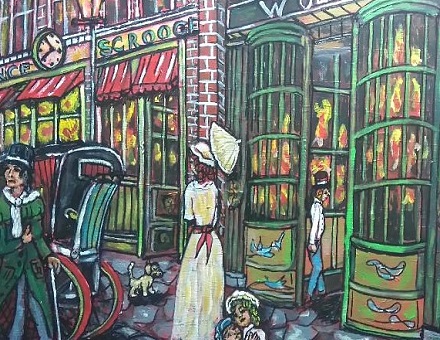

Nineteenth century shops

Shops started to develop in the late medieval period.

Glass windows started to be used in the 1700’s and became common after excise duties on glass were abolished in 1845.

After the Napoleonic wars, there was a long period of domestic peace, prosperity and population growth. Alongside this industrialisation was increasing production of many items, and products were increasingly being brought to Britain from the colonies.

The demand for food was growing, and food shopping was, for those who could afford it, an important activity. Food is perishable and food shopping might be carried out daily at a range of specialist shops such as grocers, bakers, butchers etc.

Nineteenth century shopping was time consuming. Customers were individually served; goods were kept behind the counters and often needed to be individually weighed and / or wrapped. Customers would need to go from one shop to another, then queue to be served.

The poor had little free time and generally shopped at markets and street sellers, often only weekly. Their food was basic and cheap.

Larger shops employed shop assistants, often women “between school and marriage”. They might be forced to work from 7am until 11pm, and often slept on the premises. They were poorly paid, and needed to be literate and able to calculate costs and change.

Although nineteenth century food shops were unlikely to use window displays, other shops started to. Better street lighting ment that customers were shopping in the evenings, and lighting inside the shops meant that goods could be displayed to potential customers, even at night.

Competition was fierce and regulation scarce, so some unscrupulous nineteenth century shopkeepers would water down their milk, and bakers might add chalk or sawdust to bread to reduce costs. With customers visiting many shops, and large amounts to carry, some would offer home delivery.

Bazaars and department stores

The Soho bazaar opened in London in 1816. It covered two floors and consisted of stalls and counters. Stallholders paid a daily rent to the bazaar,which specialised in clothing and associated items such as hats and gloves. These were modeled on the bazaars of the Middle East.

More bazaars followed, especially in London, including the Pantheon bazaar at a former theatre on Oxford Street (pictures, trinkets and toys) and the Pantechnion bazaar (coaches and carriages and later furniture). The Baker Street bazaar began selling horses, and then saddles, furniture etc.

Bazaars had the advantage of offering protection from bad weather.

After bazaars, shopping precincts and department stores evolved. Department stores became fashionable places for middle class or wealthy women to shop for clothing according to Historic England. Middle class women wore several layers of clothing, and wanted an extensive wardrobe for their increasingly active social lives, so demand from them was high. By the middle of the nineteenth century, department stores were to be found in all major towns and cities.

Mass production fuelled the range of goods available, although clothing was often supplied to shops partially complete allowing dressmakers and drapers to fit them to individual customers, or for the customers to finish them at home. In time, ready to wear clothes started to be sold.

Many could not afford such luxuries. Poorer people bought fabric and made their clothes themselves from sturdy fabric which would last. Their clothes were often adapted if necessary and handed on to other family members.

.